JAN SWAFFORD: A NEW ENGLAND HIKER’S JOURNAL

In August, 1970, a friend and I sat watching the sunset from the summit of Mount Liberty in New Hampshire’s White Mountains. As of that evening, I had never in my life been so dirty and so exhausted. My shorts were too tight, boots too small, shirt too thin. Due to the displeasure of several sets of muscles I’d never known I owned, my walk was a sort of sideways shuffle.

My spirit, meanwhile, was soaring over the misting valley, across the distant silhouettes of hills; soaring not like an eagle, maybe, but at least like a dazzled and eager city bird. As the sun sank below the peaks I thought with a thrill, an actual thrill in the heart: “Remember it was here you first lived in mountains and valleys.”

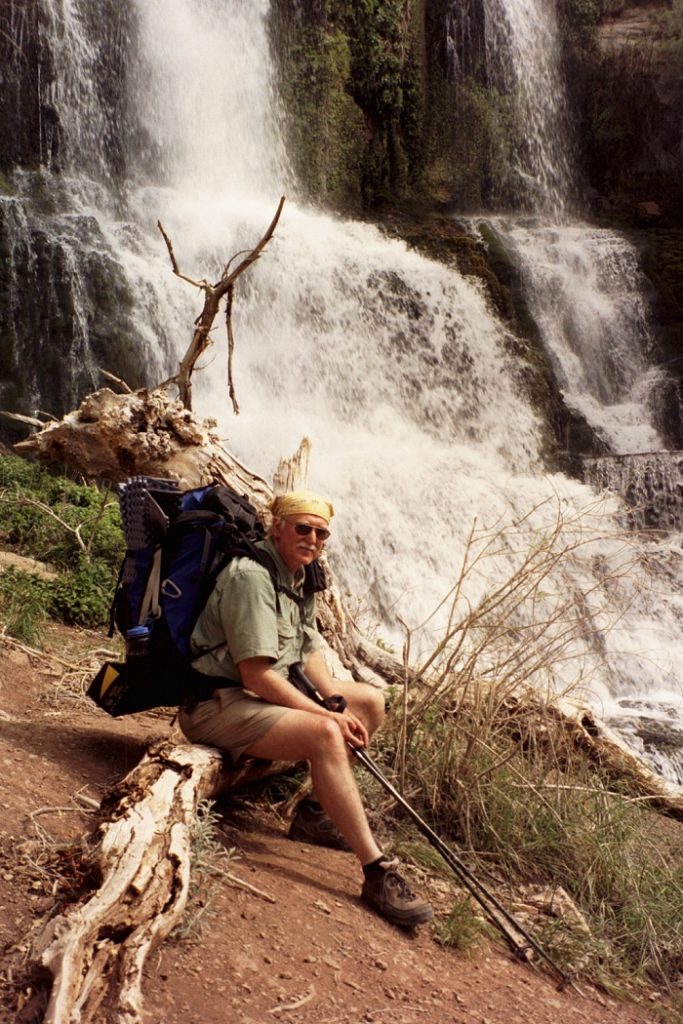

That was the first of going on fifty years of backpacking trips. Since then I’ve stood on the summits of Mounts Marcy and Washington in midwinter, watched dusk from Mansfield and dawn from Camel’s Hump in Vermont, slept alone under the stars atop little Pine Cobble above Williamstown, sat and written in my journal in the middle of a snowfield in June in Mahoosuc Notch, seen the sun go down and the moon come up from a cliff in the Grand Canyon. In all those places I felt the same thing I’d first experienced on Mount Liberty: an exaltation of spirit soaring above mortification of the flesh.

What follows, assembled around 1984, is a sequence of entries from three ragged spiralbound notebooks that constitute the trail journal of a composer and writer. They were published in the mid80s by the Hampshire Gazette, one of the first pieces of my prose that saw print. These words accumulated during the week or two a year that I was able to extract myself from the daily round of getting and spending and take to the mountains of the Northeast. They are quick sketches of insight, frustration, friendship, loneliness, growth, and awe. Perhaps they outline something of what we hikers go into the mountains and the forests to find.

July, 1970, in the White Mountains.

13 Falls. We come out of the city into the woods with a shock of recognition; instinctively we see these shapes and colors as beautiful: we sense that this is where we began; somewhere in our souls and cells we long to return.

A journal is good for these moments in the woods that are as evanescent as the flickering of a summer cloud. Such as these falls, sparkling like myriad diamonds in the sun, the play of light in deep columns of water as they caress and carve the stone: womanshapes, Henry Moores.

Thoreau Falls. A thunderstorm is approaching from across the valley. Dates like clocktime are out of place here, lost in phases of sun, rain, light, dark. Maybe that’s why tribal cultures are oblivious to change–all states in the forest are familiar repetitions, rondo form, circular rather than additive.

October, 1970, on the Appalachian Trail atop Pine Cobble Mountain near Williamstown, Massachusetts. Looking across the redgold hills I begin to understand how art rises from the union of this nature and our nature. We sense the world as beautiful or vast or varied or ominous and forge these impressions into art in ways tempered by tradition. Charles Ives, standing on his mountaintop, looked for the less obvious unities. He noted that an observer standing in one place sees a unified scene with heterogenous parts; yet the observer also feels the greater panoply out of his sight. Thus the unfinishedness of much of Ives, his music a rich-textured spiritual landscape spreading out of sight of the beholder.

July, 1971, on Vermont’s Long Trail at Stratton Pond.

Me, the pond, a dog, three young men, two lovers whispering and caressing (when I arrived this afternoon the girl was rising naked like Venus from the pond). The sun has set and moon risen over the silver sheen of the water. It’s so still that I can hear the highpitched whine of my nervous system. The conversation turns to porcupines, the temperature, the resident dog, the possibility of rain. Then, as we watch night come, words disappear into the darkening shapes like a fire’s last flame.

Time is now a dancer poised in midleap.

Bourne Pond. Birds skimming headlong over the water, ragged clouds skimming a blue blue sky, all moving effortless as thought.

Later. Hustled to Swezy Shelter–dammit, boyscouts, so picked up my rod and my staff and trudged on to Swezy Camp, old logging cabin probably, in picturesque repair. Now three randy highschool kids are reciting the grafitti on the ceiling.

On the way a meadow of headhigh grass with trees that seemed arranged and orderly–a Grecian meadow, murmuring of nymphs and satyrs. Then a bower under a pine tree: switching myths, I thought: I’ve always been a Tristan without an Isolde.

August, 1971, camped on the Long Trail at White Rocks Cliff.

I am looking down into a valley that is so perfectly beautiful in its vastness beneath a clearing sunset sky. The dark clouds are sighing away to the northeast; in the valley houselights are going on; the sun is nearly down. I smell the trees.

From the mountaintop we see the big perspective. All the grieving quarrelling suffering going on down there blends into the greater unities, into the stars. We need that perspective, now and then–to put things into their largest relations, to see what this and that share, what enfolds them. Sitting on a crag this afternoon I followed the lines of the hills, the ridges like titanic counterpoint playing across the cloudy horizon in the grand universal Symphony.

These sounds: low snarlings of trucks in the valley; distant gunshots, dogs barking; close to me, the rising and falling breathing of wind, the flutterings of a bird. Now the sky has cleared; darkening, this day’s sun a memory, the twilight sky unfurls its diaphanous veils of oranges and reds and purples. We’ll have a million stars tonight.

October, 1971, on the Long Trail at Pico Peak.

Two of us sitting here looking around and writing in identical little books, the Canadian gent and me, both of us trying to capture these moments. A quiet, perfect day. Without irony we talked Beauty and Truth, sitting before the cabin in the golden autumn sun, looking out across the mountains. Late afternoon now; we and everything are slowing down. I am reminded of my first visit to Vermont, five years ago: the same warmth of spirit, the same tincture of holiness.

Remember the hundreds of miles of hills glowing red- orange with dark green blazes of conifers at the peaks.

February, 1972, Windsor, Vermont.

Not on the trail now but rather sitting around in suburban houses accumulating foulups. Bob, Valerie, and I left a day late due to a record snowfall, I threw up all night, now Valerie with her stomachache and assorted equipment problems. Never has so much gone so dismally wrong despite such elaborate preparation.

Two days later, at Tillotson Lodge on the Long Trail. In winter, it’s poignantly back to basics–food/ warmth/ shelter. The hike up began easy and ended hard; the last part was so steep our snowshoes slid like skis. I saw the shelter and made a beeline for it across a steep incline; ended up nearly snowballing down the hill and with hands half-frozen–I was rigid with pain while they thawed.

But now we are warm and well-fed and I’ve had my pipe and all is cheerful and sleepy. With satisfaction we contemplate the temperature outside–7 above–and wish it were colder so as to brag later. Hot chocolate before bed! Droste’s!

This is something I’ve always wanted, to be in a place like this, tired and happy like this, with good company on a good day.

Next night. Valerie feeds the stove the wood we’ve spent the afternoon gathering and cutting. Outside it’s fifteen below, inside 75F. We’re warm and full again. The stove hums a low Gb, with a third-partial Db like a distant trumpet quavering in the breeze. Bob breaks wind on a perfect Bb, completing a major triad.

Next day. You’re snowshoeing down a hill wrestling a load of wood and suddenly look up and discover again the soaring curves and masses of white over everything, discover beauty all over again, remember the things that will never change, never stop being beautiful. On a good day all these things blend into one–the struggle and the preparation join with the shapes of snow and the wind in the trees to become one feeling not of doing but of being.

From today remember the quiet woods and clearings, the crystalline shadows of trees lying across white meadows still as the stillness before creation. As we neared the top of Haystack Mountain, garlands of limbs made gentle bowers of blackspeckled white under the intense blue of the sky. Bob said to Valerie as she caught up, “A black angel came down and told us we’re in heaven.”

June, 1977, on the Long Trail atop Mount Mansfield.

This ridge I am facing now is a perfect extended musical line, a melody inflected in continually varied ways in its long arc–rising out of the mist pianissimo on my left, ascending to a series of peaks of greater intensity with a forte at the zenith, sinking again to pianissimo at the end. (This was the spark that eventually produced my Landscape with Traveler for orchestra.)

Spending the day on Mansfield, moving between large and small, the old associations return: the polyphony of the ridges, the animalshapes of the hills, the myriad forms and variations of forms held together by the sweep of hill or limb; the sense of vast space contained by the hills like wine in a goblet; the grainy and eternally varied symphony of the insects; the intuition of ancient geological time and forces; the complements of rocks and plants–mottled gray and infinite shades of green.

There is a new understanding today, unnoticed in my lone-wolf younger years: the ages of human presence in the mountains, the cultures, the generations of men and women searching on these rocks like the generations of insects.

Later, at Prospect Rock above the Lamoille Valley. Two days ago I pulled into Sterling Pond Shelter in a godawful downpour, put on my sitting clothes and settled down to write some music. After a few notes I looked up to find the sky miraculously clearing. Music vanished from my mind, I danced around anxiously in front of the shelter consulting the clouds, and finally, glutton and sucker that I am, I hit the muddy trail at the first sign of sunshine. Today the wonderful loose free sunny downhill day, now this cliff with the hazy green pastures and lazily curving river spread out below. I’d forgotten how wonderful it is simply to walk through a dappled forest, to bath naked under a chill waterfall.

Next day. Walking this afternoon I thought for some reason about current movies depicting the thirties: they often make the film itself look like photos from the thirties. It struck me that old photos and movies–and earlier, paintings–are what form our imagination of an era. For us, the thirties is an age of sepia and faded black-and-white.

Next day. Sitting now on the windswept summit of Haystack, looking south down my path over the Green Mountains: Tillotson, Belvidere, Madonna, Mansfield, Camel’s Hump, Ira Allen. At last on my last day and last summit there is clear blue sky and good visibility. This is a gentle peak, its spruces whispering intimately; forty feet above me a wisp of cloud is continuously born and dissolved.

Later, at Hazen’s Notch Camp. Arrived to find a five-year- old girl standing in front of the cabin screaming. An older girl appeared from uptrail and told me tearfully about four who’d headed downstream. I rounded them up, marched them out to the road, loaded them into a passing furniture truck for delivery to the local police. They said they’d been on a school hike. If so, it’s five hours since they’ve been lost and the incredible dimwit of a teacher hasn’t noticed.

Last night at sunset I was on a fire tower on the summit of Belvidere: howling wind, torn sky with the sun huge and red in a distant parting of clouds, the rhythms of mountains and valleys in every direction–and the song of one whitethroated sparrow.

I wanted to finish the Long Trail this time, but no dice. I’ll be back.

October, 1978, on the Long Trail at Mad Tom Shelter.

Autumn’s colors stand out each in bold relief in a stand of mixed trees–the yellows, reds, oranges and greens set one another off, outlining each tree. The most striking thing is how the framing yellow turns spruces to an electric blue-green.

The leaves are going early and fast, the hills faded from the loud yellows and reds of last week to rust and spreading gray. It is the flowering before death, the convulsion of beauty before the falling away, the evanescent sweet-sadness of autumn.

June, 1982, on the Mahoosuc Trail at Gentian Pond.

First backpacking trip in four years, since that of the previous page when I was still getting used, if one does, to being broke and divorced and was not yet plagued by a bad back.

This pond is radiant with thousands of gentians blooming all around the bank, and there are fleshy purple flowers out in the water. From the bluffs above, a soaring view; the towns look like an odd grey lichen on the solid green floor of the valley.

Two days later. Arrived at Full Goose Shelter planning to go on if this place were as glum and buggy as the last. Proved cheerful and bugless. So instead I went dayhiking down into Mahoosuc Notch, jumping like a jackrabbit without the pack. At the bottom I was nosing around, wondering if this was what the fuss was about, when a step brought me to the brink: the snow field, the mossy boulders, the icy wind that seemed to burst from the earth.

Next day, in Mahoosuc Notch. After crawling and squeezing my way through narrow corridors of stone, I’m perched eating crackers and good Vermont cheddar on the same boulder where I sat yesterday. A solid rock wall sweeps grandly up to cliffs on my right; on my left Mount Mahoosuc arches into the clouds. The air is resonant with the rush of wind and the cries of hawks prowling the cliffs. Around me are boulders wildly tumbled and hummocks of snow glistening in the summer sun. Some of the trees are still in bud. There is an uncanny aura in this place, a secretiveness, a sense of time out of joint.

Next day. I need to teach myself how to enjoy the surprises in life, even the foulups like the miserable trail relocation at the beginning of this hike. It’s the unexpected that keeps life dynamic, that insures things will never become too controllable, that keeps us humble.

Remember Speck Pond, the notch at the far end looking over the vastness of the valley, the slow dreamy nocturne of peepers and bullfrogs, the dip in the freezing water, screeching with the cold and loving it.

August, 1982, in the White Mountains.

A first summer hike with friends–composers Lew and Greg. With other people there is the constant babble of observations acute and otherwise, a tendency to marvel at the commonplace, but also the unspoken sense of shared experience–the joy, the concomitant struggle and pain. Being with a group dampens reflectiveness but makes for learning more: bits of lore, new tricks, expanded powers of observation. (Alone I would never have noticed the raspberries, and they were so good, so good.)

Two nights ago we were at Imp Shelter, me more beat than I’d planned to be, and spent the evening chatting with, 1) lovely Connecticut housewife and hubby, both squeakyclean and even perfumed, eating couscous, yet apparently stalwart hikers; 2) caretaker kid, smartass but also smart, who rambled about Thomas Mann and dipped snuff; 3) a music librarian of the Library of Congress and his musicologist wife (“Aspects of Rhythm in 12th- century Polyphony”), both of them as grubby as groundhogs, as were we three composers. Among us all, an outre evening around the old campfire.

October, 1985, on the Long Trail at Harmon Hill, overlooking Bennington.

This is as good a time and place as any to write down a current credo:

Let’s stop trying to figure out the gods. It’s a hopeless and fatuous endeavor, like an ant trying to figure Einstein, magnified to infinity. The gods do not need our help or our feeble hosannas. What we should do instead is to marvel, and above all to take care of one another. What there is of divinity–and that is something I do believe in–we will find within ourselves, and we adumbrate the divine light in acts of sympathy, pity, compassion, love. If we pursue these we’ll survive, and be as blessed as we’re capable of being.

August, 1986, on the Long Trail at Hazen’s Notch Camp.

It was from here that I left nine years ago, having worked my way up the Long Trail section by section starting in 1971. I planned to come back that year and finish the trail, or maybe the next year. Then life intervened.

But I never forgot this brown cabin by the brook, and the trail stretching away north. So yesterday I started at the Canadian line and headed down, and here I am come full circle.

I remember so many moments on the Long Trail over these fifteen years. There were the first three Appalachian Trail hikers I met, at Griffith Lake: two kids who’d never hiked before and who had by then walked 1600 miles with cheap Sears equipment and no food but Kraft Macaroni and Cheese; their buddy, ex-Air Force scientific hiker with custom boots and protein powder, was in no better shape. I asked the latter why he was doing it. “If my sister’s in the downstairs bathroom,” he said, “I’ll be in shape to run right upstairs.”

I remember Camel’s Hump in early morning, clouds lying in valleys all around. Bourne Pond on a still summer afternoon, birds skimming low over the water. A pretty girl washing her cooking pots in front of Skyline Lodge. A distant inexplicable horn playing Mozart at midnight from the top of Pico Peak. The rippling panorama of hills seen from Mt. Horrid Cliffs near Middlebury. A night alone under the stars at White Rocks Cliff (and waking in the middle of a thunderstorm). The day in 1970 when I looked north to Vermont from Pine Cobble and idly thought wouldn’t it be nice to walk the length of the state.

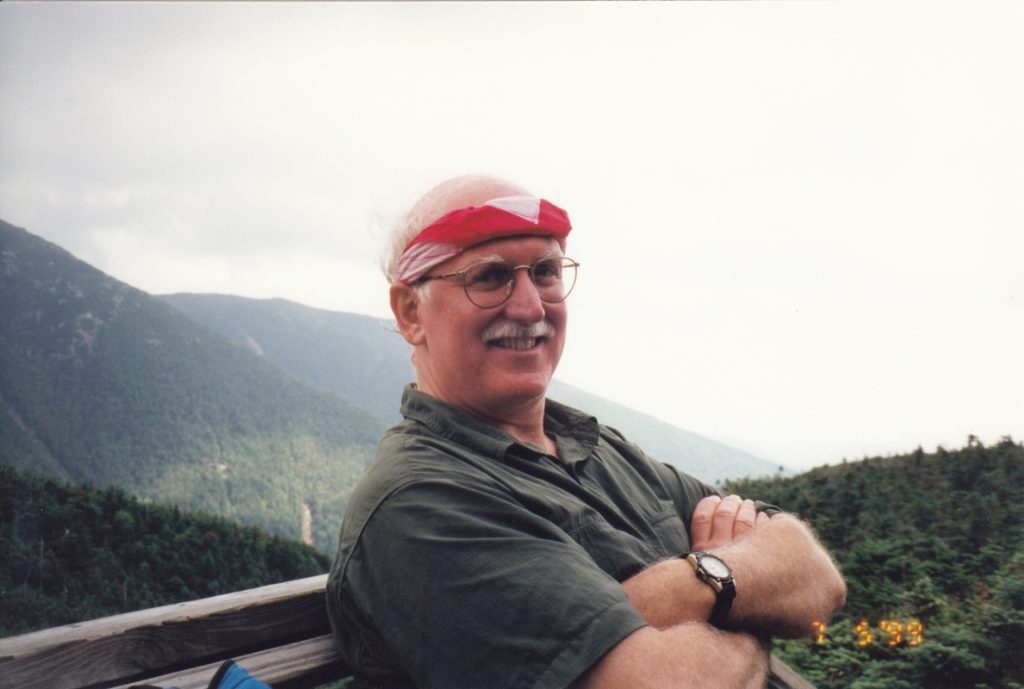

I’ve done various things in my life, heard my music played by symphony orchestras, published books. But now I’ve finished the Vermont Long Trail, and I take considerable satisfaction in that. Maybe among other things it shows that, like the mountains, life’s interventions can be surmounted–one step at a time.

Now I can get my end-to-end patch from the Green Mountain Club. I’ll ask my friend Mary to sew it onto my pack, so it’ll be a neater job. I plan to look at it over the years with a good deal of pleasure, and with unabashed sentimentality.

POSTSCRIPT, 2017—

As you can see, my observations when I’m hiking tend to be in a rhapsodic and poetic direction. Likewise my notes in the logbooks that are sometimes placed in trail shelters. In regard to that, here’s an object lesson in the power and likewise the ambiguity of prose.

As of some 25 years ago I hadn’t hiked in New England in a while, so I decided to do a weeklong trek that started on the Long Trail in Northern Vermont and ended at a cabin on Camel’s Hump. When I set out I was elated to be back on in the woods and in one of my old haunts, so I was writing especially ecstatic stuff in the shelter logs, meanwhile noting that I was going to be spending a week on the trail. Then it started to rain. Rain, rain, rain. After a couple of days I decided, the hell with it. I’ll go back home, wait till the rain stops, then hike two or three days further south, ending at Camel’s Hump.

So I did go back, actually for only a couple of days. At the end I was beside the cabin gearing up to hike out when a young guy appeared on the trail. I could tell he was a long-distance hiker, probably an Appalachian Trail trekker come down from Maine. Long-distance hikers tend to be tan and lean and their clothes have a certain look of permanent grime. This guy looked beat. He dropped his pack and sat down at the table with a sigh.

We chatted a bit as I got ready to go. He told me he was tired because he’d been really pushing it, despite the rain. How come? I asked. I’m trying to catch up with this girl, he said. Oh, she’s your hiking partner? I responded. No, he said—actually I’ve never met her. But I think she’s really something. I was scratching my head. How come? I asked. I’ve been reading stuff she wrote in the shelter logs up north, he said. Oops, I thought, and asked: What’s her name?

Jan, he said.

I should have let him down easy, but I was too flabbergasted to think. Oh, that was me, I blurted. Now, mind you, I was only about 45 at the time, but I was still a white-haired bald guy with a pot belly. And this guy had been humping it hard for a week in the rain trying to catch this sweet poetic girl who undoubtedly grew more beautiful and bewitching with each passing day. It couldn’t have been much worse for the poor guy. The look on his face could spark a novel.

I hope in later years he has found this as funny as I do.