Essentially, in the beginning, it was this: I was 68 and wanted to do this trek before it was too late–the Royal Arch Route, generally agreed to be the hairiest of the regular trails in Grand Canyon. Examined in ordinary grownup terms, it was no place for an aging musician and writer to get himself into. There’s a lot of clambering over large boulders in a streambed and some episodes of, as it is termed, “breathtaking exposure.” “Exposure” meaning the close proximity of drops that, if you fall off, you tend to die. Its side trail, to an exquisite little canyon called Elves’ Chasm, is the scene, the Park Service description helpfully tells us, of “a number of gruesome accidents.”

The Royal Arch Route is also noted for its beauty, the climax being the eponymous and splendid natural arch in the middle of the circuit. It was only “discovered” in 1959, by legendary Canyon explorer Harvey Butchart (Native Americans have presumably known about it for millennia). After the arch there’s a much-dreaded rappel down a 20-foot cliff. I’d been dreaming about the Royal Arch Route for years. Meanwhile in my annual spring Canyon treks I had completed most of the other, easier, traditional trails. This was to be my twelfth Canyon trek.

Those trips were not without incident. Talk to any old hiker, you hear about misadventure. In eleven Canyon treks as nominal leader I’d seen an old friend take a little misstep, trip, and hurtle down a slope that could have killed him—but didn’t, as it happened. On another trek in a heat wave a member of our group fainted in potentially fatal condition from heat sickness. There were some bad hours, but the end she didn’t die either. We’ve encountered various rattlesnakes, experienced the entertainments of severe dehydration, and so on. I knew the risks pretty well. I was also a hiker of 45 years experience, in decent shape for my age, with pretty good knees, and over the months I’d spent hiking in Grand Canyon I and everyone involved had lived to tell the tale.

So I know what the Canyon entails. It isn’t the walking or the long haul up and out, it’s the desert heat and the water and the distances that can get you. We all have our ways of dealing with it. As I tell people, I’m not about strength, I’m about finesse. (First rule of finesse: You can always walk slower.) I know how to calculate the water. Preparing for the Royal Arch I’d done a decent amount of spring training to get ready, more than usual. As I was to be reminded this time, however: when potential disaster looms, finesse only gets you so far.

From the Park Service I got my hike reservation for Norm Bendroth and me the usual five months ahead. Given the thousands of aspirants, that’s what you do. Norm is an old friend and hiking partner, a Congregationalist minister who wears it lightly. He’s strong as a bull. My nickname for Norm: “Trail Animal.” To prepare, I read every Royal Arch trip report I could find online and studied the risks—not so much the actually easy rappel as before that, the boulders and pouroffs in Royal Arch Creek. And of course, let’s not forget the exposure. In reports I’d read about a spot of severe, aka breathtaking exposure just before the rappel. Unseen, that spot had gnawed at my imagination for years.

I was, in short, a little bit afraid of this trail. Which whetted my appetite for doing it. Before it was too late.

In the Royal Arch creekbed I knew we were going to have to scramble over boulders and ledges, pass packs down on a line, maybe wade in water, etc. There is one spot where there’s an impassable pour-off in the creek and your choices are, to the left, what is familiarly called the Ledge of Death, a stretch where you tiptoe sideways on a four-inch foothold over a sixty-foot drop, with not much handhold (as one veteran put it: you’re grabbing an A-cup when you you’d prefer a D-cup). To the right of the pour-off, however, is a crumbling trail with a squeeze-through bit known as the Rabbit Hole—and that route is relatively safe. Between the alternatives of Ledge of Death and Rabbit Hole, most hikers choose the Rabbit Hole. We sure as hell planned to.

Meanwhile, in friend Norm I had a hiking partner who I knew was unflappable and strong and experienced, who could lend a hand if necessary. Brother, was it necessary. Likewise the kindness of strangers. The strangeness of strangers was another matter.

Our intricate comedy of errors that kept threatening to become something far nastier is a sort of mini-saga, with a varied cast and episodes of comedy both light and dark.

We knew about the hour and a half drive on 35 miles of steadily deteriorating dirt roads that are the route from touristy Grand Canyon Village to the remote Royal Arch trailhead. We rented an SUV with good clearance. When we got there the two-foot-deep ruts in the middle of the road got our attention sure enough. You have to hope the road is dry, not muddy, because then you can get hopelessly stuck. For us it was dry and firm, at least. In the bad spots you inch along, trying to keep the tires on the narrow bits between foot-deep ruts. It was one of the damnedest tracks calling itself a road that either of us had ever seen. Actually, in the end, it was kind of fun.

We made it to the trailhead without incident. So there we were, in a place I’d dreamed of for years. Norm locked his cell phone and wallet in the glove compartment and we geared up. As usual I stashed my wallet and single electronic car key in my pack. In that casual act, the saga began.

The first day’s hike down the South Bass and Royal Arch trails was pleasant and as they say uneventful. The prospects of buttes and canyons was glorious as usual, the weather sunny, the trail cheerfully downhill. For the moment temps were some ten degrees cooler than usual in mid-May, in the 80s rather than 90s. As always in the desert, that made a critical difference. After a steep descent of a mile and a half there’s a confluence of trails. We turned west on the Royal Arch Route for a long traverse gradually descending toward the creek. At the trail junction we cached two half-liter bottles of water in case we needed them when we circled back to that spot on the return. Boy howdy, did we need them. Or rather Norm did, because I would not be present at the time.

On the second morning, after clambering over an ungodly half mile of rough talus, we reached the dry upper section of Royal Arch Creek and began another gentle descent on smooth rock, watching for water as we went. Now we were in a tight canyon hike, the beauties more intimate. We knew it would be dry for a while. I’d read that there was reliable water near the arch three miles down, also water in potholes before you get there—but we didn’t know where, and the miles were going to be slow with all the clambering. We also knew that this had been an unusually dry spring, so the potholes might have dried up, or what water was left might be too skanky to consider unless you’re desperate. At that point we had enough water and weren’t planning to be desperate.

Here I’ll note that I have a peculiarity of mind that can serve me well in my capacity as a composer and writer, but not always so well in the rest of my life: I get an idea lodged in my head and that idea can overshadow everything else, such as what is actually in front of my face. You can ask my ex-wives about this. For some reason I was convinced from my reading of trip reports that the Ledge of Death/ Rabbit Hole bypass was a mile or two later, in the middle or at the end of the boulder scrambles in the creek.

That’s what was in my head concerning the Rabbit Hole. As we innocently made our way down the creek we came to an impassable pour-off. After a whatthehell moment Norm spotted a rudimentary path up the slope to the right around the impasse, marked with rock cairns. We forged up, then made our way along a rubbly but decent trail on a steep but only modestly scary slope. Any minute we expected to find a trail back down to the creek. At one point we came to a small opening through which we had to pass our packs and crawl. “Gosh!” I said brightly, “this is a lot like the Rabbit Hole!” Of course, this wasn’t like the Rabbit Hole, it was the Rabbit Hole. This pour-off was not the last obstacle in the creek, but rather the first. That simple concept never entered our minds.

Often a single mistake sets off a train of them. A touch of uncertainty invaded our awareness. Because we didn’t recognize the Rabbit Hole when we were in it, we didn’t look hard enough for the trail down to the creekbed just after it. Instead, we followed what became a splendid false trail, well supplied with false cairns, high above the creek. After another 45 minutes or so, trail and cairns petered out in the middle of nowhere on a crumbling trailless slope. Realizing we were on a goose chase, I looked down and told Norm I thought I could see a spot below where we could get down to the creekbed. Okay, Norm said. He’s an agreeable guy. We made our way down the bouldery cactusy slope and found, naturally, an impassable cliff above the Royal Arch creekbed, where we needed to be.

At that point it was around noon. We were getting tired and running low on water. We rested and ate lunch, which was at least one good idea. I suggested bushwhacking upstream along the cliff to look for a way down into the creek. No, Norm sensibly said. Unpleasant though it may be, we need to clamber back up to the false trail and retrace our steps, because that will reliably return us to where we went wrong. It took us the better part of an hour of miserable scrambling to get back up to the bad trail. After a half hour or so retracing our steps Norm discovered the trail down to the creekbed that we’d missed. By then it was midafternoon.

Our excursion on the false trail had cost us over two hours, much of our energy, and most of our water. Being low on water in the desert is the definition of what you do not need.

We began forging again down Royal Arch Creek and, one after another, dealt with the rock scrambles we’d been anticipating. At one point to go over a fifteen-foot boulder you pass your pack down on a line, slide several feet down on your stomach, and catch a rock with your left foot at the bottom. I passed my pack to Norm, slid several feet down, caught the rock with my left foot, put out my right foot for balance, found air and toppled. My left foot catching in a seam between rocks saved me a five-foot drop onto my head in the creekbed that might have broken my neck—or maybe cleared my mind.

At a couple more spots we had to tie the nylon webbing to our packs and pass them down, or the scramble would have been riskier. This is easy enough. You slide the pack down the incline, your partner secures it, you toss the line down. Meanwhile as the afternoon wore on we were getting steadily more tired and dehydrated. Finally we were running on fumes, numbly putting one foot after another. From dehydration our voices had become a hoarse croak. There kept being no water in the creek. I remember thinking that this would all be kind of fun if we hadn’t gotten delayed on the bad trail and if we weren’t tired and thirsty and anxious.

Were we scared? Not particularly. We knew there was going to be water in the creek sooner or later, and we knew that you didn’t have to be a trained rock climber to get over the boulders. We figured we could keep going after dark if we had to. (We didn’t know yet that we had only one functional headlamp—Norm, bless his heart, hadn’t checked his batteries before he left and they were nearly dead.) Meanwhile—this was the luck of that day—, temps remained in the mid-80s. So as we forged down the creek we were dry but not dangerously dehydrated, beat but not really bonked. This being a creek bed, there were occasional patches of trees and close walls and shade.

After we’d plodded and scrambled for an hour or so, as we were searching for the route for yet another downclimb, Norm called out that he saw water in a pothole below us. Gallons of water! he cried. It took some dicey scrambling to get down; we passed packs and slid down a rock face on our butts, clutching my nylon webbing for safety. When we got there the pothole proved to be a gloriously skanky affair, the water dark brown, tadpoles in residence, also a couple of frogs and an enormous white scorpion. At this point it all looked wonderful. There was flat rock beside it where we could sleep.

We began filtering the water with our two hand pumps. The tadpoles and the scorpion didn’t seem to mind. (We thought the scorpion was dead, but it wasn’t—it was gone next morning.) Norm’s filter was not made for things like this; the water came out of it brownish, but at least didn’t taste too disgusting. I had a ceramic filter that was slow and had to be cleaned constantly, but it gave us fresh-looking water and would not clog with grit as Norm’s was inevitably going to. As dusk came on we discovered that Norm’s flashlight was nearly dead.

After pumping water for the better part of an hour, we made dinner on my camp stove and got ready for sleep, laying out our sleeping pads and bags on the rock. We slept very well.

Early next morning as we were eating breakfast we heard yelling, somebody asking if there was water. We yelled back, yes, there’s a pothole. In a minute a bearded young guy appeared from around the corner. He was so dehydrated that his voice, like ours the day before, was a frazzled croak. Can I use your filter? he said. Sure.

For the next half hour he pumped water from the skanky hole and talked. Let’s call him Jake. “My girlfriend wants to kill me,” Jake said. He did variations on that for quite a while. She was waiting in their tent a half hour above us. He’d brought her down the creek on the notorious Point Huitzil route, they had ended up clambering over scarily exposed rocks by headlamp and running out of water. She had half a liter of Gatorade left but wouldn’t share it with him. She’d been screaming abuse at Jake pretty much continually since yesterday: idiot, incompetent asshole, and so on. In the course of their relationship over the past months, he told us, they had hiked many miles, she had taught him rock climbing. But this looked like the end. He didn’t know if she would be waiting for him when he went back up. Finally, with several liters of water he’d filtered with our pump, he thanked us and climbed up and away. We figured we’d never see him again.

At least in the ensuing herd of snafus we didn’t get sick from the water. Norm and I packed up and continued clambering down the creek. Of course, in a half hour or so we came to clear flowing water. Just before it there was a bit of scary ledge, inching along sideways with a short but nasty fall underneath. I concluded in the middle of inching that this was the Ledge of Death. I was quite wrong. It was a run-of-the-mill scary ledge. Later I dubbed it the Little Ledge of Near-Death. It was only next day that I put one and one together and realized we had been through the Rabbit Hole early on.

After a rest at a sweet little pool we were forging blithely on when I glanced up and realized, in disbelief, that we were under the Royal Arch. The trail down to it is a spur off the main trail, but we had missed the turnoff out of the creek and blundered onto our destination for the day. But this was great news, after all! We dropped our packs and prepared to relax for the afternoon and night.

To our surprise, in early afternoon Jake and his girlfriend arrived. We’ll call her Elena. They were semi-reconciled, at least speaking. She still intended to kill him, she told me. What are you going to do it with, I asked politely, your hiking poles? No, a rock, she said. But they seemed to be sort of getting along. We chatted pleasantly. She said she had just completed something like a thousand-mile solo hike on the Pacific coast. Her next ambition was to spend some four years on a hike from South America to, as I remember, Alaska. She had asked Jake to join her on this historic trek. He was skeptical, and so forth and so on. All this amounted to clues of coming weirdness, but we didn’t notice. She told me about her hiking website. (On my return home I couldn’t find such a website.)

The rest of the day was uneventful in the best way: calm and lovely. The Royal Arch is a marvelous, many-layered, stately piece of limestone. I teared up at the first sight, having dreamed of this place for so many years. I spend hours lying on the rocks contemplating the arch’s intricate folds, the blocks of stone that had flaked off over the eons. I thought about the ten oceans that had covered this area, advancing and retreating, the remains of the oceans’ shellfish forming the limestone I was looking at. Here were millions of years laid open before our eyes. Jake and Elena clambered up to the top of the arch, but we were too lazy to try it. We all had a good night’s sleep.

So far the hike had involved its unpleasant bits, but was otherwise going well enough, if anything better than I’d expected. So far.

Next morning Jake and Elena set out from the arch ahead of us, which turned out to be fortunate. Norm and I got out about 7 AM and discovered that in climbing back to the main trail we had to clamber up some of the obstacles we’d clambered down the day before and hoped to have seen the last of. But we were eager to get to the rappel and down to the river, which appeared to be the last troublesome part of the hike. The exposure I’d read about above the rappel was never far from my mind.

As we forged upward we heard Jake and Elena shouting. We looked up to find them on the slope above us, on the trail going toward the rappel and the river. They told us where the turn was out of the creek, which we’d all missed on the way down and they’d missed again on the way up, so they’d had to double back. This saved us some gnarly uncertainty, because we might also have kept clambering up past the turnoff.

With their help we found the turn out of the creek, trekked up the steep climb (my uphill pace stately as always), then commenced a mostly gentle trek flat and downhill toward the rappel, though some of it inches from a cliff. The Park Service trail description had a “long hour” to the rappel. It was closer to two hours. Just before the rappel lay the bit of exposure I’d been dreading for years. I had gotten the impression that it was a combination of rubbly loose rock—called scree–and a cliff, which is my least favorite situation. In my hiking career I’ve had a couple of potentially final encounters with scree on a slope near a cliff. Once, in the Alps, I was flat on my stomach trying to hold on to a little rock and inching toward an abyss when two men appeared to save me. I never forget that moment.

And now, dear reader, comes the little irony of our story. When we got to that bit of exposure I’d been dreading for years, I immediately realized it was not that bad. It was a ten-foot downclimb that was, yes, a few steep feet from a cliff at the bottom, but the handholds were excellent—spiky volcanic rock that might bloody your fingers, but was the opposite of slippery. Norm went right down with his pack on. I elected to tie webbing to my pack, as we’d done several times before, kick it over the edge for Norm to secure, then make the easy clamber down.

Communication, communication, communication. That was the crux of the issue here. I tied the nylon webbing to my pack, as I’d done before. I kicked it over the edge, as I’d done before. I lowered it down toward Norm as usual. Finally I couldn’t see my pack, but below me I saw Norm lean over to secure it. He said something vague that I interpreted to mean I’ve got it. I neglected to say four easy words: Have you got it? Instead, as I’d done several times before on the trip, I casually tossed the webbing down. I remember thinking that we were getting to be old hands at this pack-passing stuff.

Looking over the ledge I saw my pack tumbling downward end over end, trailing the webbing. I screamed Grab it! Norm couldn’t grab it. It had never been firmly in his hands. In silence we watched the pack bounce down six feet and take wing over the edge of the cliff. It sounded like this: crunch, crunch, a second of silence, then from below whump, another second, whump again. Silence.

We stood for a moment in shock. My pack was gone. My whole entire mammyjamming pack. If Norm had hurled himself to grab it, he would have gone over the cliff after it. The aforementioned, bitter irony: the exposure above the rappel that I’d been dreading for years turned out to be no problem for my person, but a fatal problem for my gear. In forty-five years of backpacking I’d never lost anything. Now I’d lost everything.

One at a time, the implications began to crowd in. Too many implications to take in at once, but starting with the simple part: four days into a desert wilderness with at least two more days to get out, we had lost half our food, half our canteens, our only camp stove, all my sleeping gear and most of my clothes, our only functional headlamp and only reliable water filter, and assorted other stuff. Including, come to think of it, my wallet. Oh, and sweet Jesus, the electronic car key. That meant that when we finally managed to struggle up to the rim at the end of the hike, the road to civilization was 35 miles of baking, waterless, rutted, sparsely traveled dirt.

The fun was done. Now the game was survival. We didn’t speak what we both knew: it was a hell of a fix, the fix we were in. Not enough food, not enough canteens, no stove so no way to rehydrate most of the food we did have, nothing for me to sleep on or under, no flashlight, no water filter, no first-aid kit, and so on and so forth. There were distinct possibilities for danger and still better possibilities for wretchedness, as in shivering all night, staggering along for miles without water sort of wretchedness. As in falling off a ledge in the dark, drinking unfiltered river water, and so forth and so on.

But, OK! All right! We’re resourceful! We’re tough old buzzards!! We ourselves didn’t go over the cliff!!! Examining the slope below us, I saw that maybe we could make our way to the bottom of the cliff and find my pack. It would likely be exploded from the fall, but also might not. In any case, we could salvage important stuff: canteens, food, stove, sleeping gear, flashlight, day pack, wallet and car key. It hadn’t sounded like the pack fell that far, maybe less than a hundred feet. I climbed down to join Norm and we took another look at the slope beneath us. The first thing we saw was my foam sleeping pad sitting on a ledge. That provided a bubble of hope.

First we had to get down the rappel, often dubbed “infamous.” We weren’t sweating it. There were ropes left in place there and we had a climbing harness that was, thank the hiking deities, in Norm’s pack. Both of us had rappelled before, though to be sure not in decades. When we got to the rappel it took us ten minutes of fumbling to figure out how to rig the harness, more time to get the rope fixed right in the carabineer. But soon enough we were both down. Something else that could otherwise have been fun. From above the rappel I’d tossed our hiking sticks down as usual, and that had been another bad idea: Norm’s ended up bouncing off the trail to the edge of a cliff, one of mine was stuck in a tree on a slope beside the cliff. We got all the sticks back, but one of mine had lost its lower segment and was ten inches short. I poled with a limp from then on. This was the first intimation that the gods of snafu were not done with us.

Once down the rappel we set out offtrail to find the cliff and my pack, bushwhacking down another rough bouldery slope. After ten minutes of scrambling I yelled to Norm: I see it! A bit of blue in the grass under a tree! My pack being blue. We clattered down to the spot and found it was the blue top of a canteen. We assumed it was one of mine since it was the same brand, and we also assumed that it lay in the debris field of my pack. But it wasn’t my canteen or my debris field. What we’d found was a graveyard of canteens that over years had fallen from the same cliff my pack had gone over.

In an hour of searching all over, we didn’t find my pack. Just more canteens. Finally, having as far as we could tell covered the whole slope—a sliding, stumbling misery, with cactus as seasoning—we gave up. We gathered three canteens to take with us because we knew we were going to need them. In the desert, water is life and canteens hold the water. We should have picked up more canteens. We were going to be on the Colorado River that night, but the following night was potentially a dry camp, and 24 hours of safe hiking in desert heat requires about seven liters a person. Norm had only his own canteens, totaling seven liters. We’d added three more from under the cliff, but that wasn’t enough. We still had his water filter, but I knew it would clog up before long, and it did. We’d be drinking straight from the Colorado.

The trek down to the river was depressing but uneventful. We walked in stunned silence. As we reached the sandy shore we saw Jake and Elena standing looking up toward us. When we got to them they were laughing with relief. They’d gotten worried when we didn’t appear and were about to climb back up the steep slope to look for us. Um, it’s not really good news, we said.

When they heard about my pack Jake and Elena were instantly sympathetic. They went into rescue mode. They were both experienced hikers and, they told us, trained EMTs. They began giving us what turned out to be critical help and advice. Elena lent us her water filter, which meant that for the time being we didn’t have to drink straight from the river. Flag some rafters down, they said, they’ll probably give you stuff. On cue a flock of rafts appeared. We flagged them down. The leader was exceedingly helpful. From them we got two canteens full of ice water, a rudimentary day pack, some power bars and the like, including a bag of goldfish crackers, and a fleece blanket. In the next days each of those items made our lives, mostly my life, significantly less miserable. We were overwhelmed by the kindness of strangers.

Jake had a GPS and allied gadget with which he could send short emails. He emailed his father, who got to work looking for help. He emailed the park rangers asking for a ride for us from the trailhead two days hence. He emailed Norm’s wife telling her to call the rangers. (Norm’s wife had no idea what rangers were meant, hadn’t read the trip details Norm left, and freaked. You don’t want to get a message from unidentified “rangers” mentioning an undefined “problem.” She began planning Norm’s funeral.) The emails were a hassle because communication with the satellite was sketchy. For an hour Jake walked back and forth along the beach holding his gadget in the air, looking for a connection.

Jake and Elena insisted on heading up and looking for my pack. Don’t do it, we said. It’s not your problem, you won’t find it anyway. Stick to your own plans, go out to beautiful Elves Chasm, spend the afternoon dipping in the spring there, we’ll be fine. They insisted. They set out, and after an hour returned with of course no pack. It’s not too late for Elves Chasm! we said, but they didn’t feel like it. We drifted toward dusk chatting awkwardly, Jake trudging around trying to get a satellite connection, me dreading the prospect of trying to sleep in dirt with only a fleece blanket over me when the temps by dawn would be in the 50s at best. At least here on the beach I’d be bedding on sand.

As the hours went on we noticed an evolution in Jake and Elena’s attitude, from concern about us back to their own concerns: Do we try to finish our hike as intended (they were already behind their permit itinerary when they met us) or bag it, stay with Norm and Jan, help them out, give them a ride back to civilization at the rim?

But after all, their not going overboard with us was only proper, Norm and I thought. We’re not in serious danger at the moment, and with the help we’d already received—above all the rafters’ daypack, canteens, and blanket— it looked like we had a decent chance of getting to the rim in two days without too much danger, though it was likely to be a hot, thirsty, unpleasant business. And of course, getting to the rim wasn’t to get home but only to a locked car and a long dry road. But we didn’t want to be a burden to Jake and Elena, and they’d given us important help already. The hope was that a ranger would meet us at the rim, after we informed them via Jake’s email when we’d be out. But that was no sure thing.

From that guardedly hopeful point the situation drifted steadily downhill.

For the moment, at least, at the river we had all the water we wanted, and their pump to filter it. Our next night’s campsite in Copper Canyon nine miles away, though, was uncertain as to water and a subject of concern under the circumstances—for them as well as for us, because they were planning to camp there too. Copper Canyon may or may not have water, and you have to descend off the trail to find it. The sure thing was to keep going past Copper Canyon and down to the river—but that was a strenuous four miles further, making a 13-mile day. And the temps for tomorrow we knew were going to be back up to normal, meaning in the 90s and getting hotter as you descend. In those temps we all knew the drill: you start walking at dawn, hole up in the shade around 10AM and wait out the heat until 4PM. High temperatures suck water and energy out of you and mess with your judgment, with potentially fatal consequences.

At dusk I addressed the problem of how to bed down under the stars in beach sand with as little misery as possible. I didn’t expect the results to be comfortable enough to actually get any sleep. Even on my usual plush sleeping gear—two pads, an inflatable and a foam, plus a down bag—I usually sleep fitfully. As dusk faded I decided I needed to dig a butt-sized trench in the sand, test it out and refine it, then scrape out a slope for my back. It turned out to work pretty well, actually verged on comfy. And I had the marvelous fleece blanket from the rafters to put over me, though I knew that by the middle of the night it wouldn’t be enough. In the Canyon you go to sleep in high temps, then by morning it can be forty degrees cooler. I also knew from experience that an overnight shivering on the ground is a uniquely disagreeable experience. I went to sleep with nothing over me, woke up in a couple of hours and pulled the fleece blanket over me, woke up two hours after that shivering.

I waked Norm and begged clothes. (He had his sleeping bag and inflatable pad, though the latter was flat, having sprung a leak. As usual he was sleeping fine.) From him I got a fleece sweater and a heavy t-shirt and his ground cloth, all of which I put on sequentially over the rest of the night. By dawn it was his skimpy ground cloth over everything that, barely, kept me from the shakes.

Our breakfasts having gone over the cliff, next morning we had half a freeze-dried dinner, hot water to rehydrate provided by Jake’s stove. It turned out to be our last more or less full meal in two days. By this point Jake and Elena had decided not to hike to the rim with us, which we all knew was going to cause us problems if no ranger turned up. But that, again, was not their problem. Meanwhile they were beginning to get a bit prickly in general, as much with each other as with us.

But they were expecting to meet us at the next campsite in Copper Canyon, the one with the dicey water down from the trail, at the old Bass Camp. Previously I’d been given email directions by an experienced Canyon hiker about how to get down to that one-time miner’s camp in Copper Canyon, where usually there was water to be found. But there might not be any water now, because of the dry weather. Moreover, my advisor’s detailed directions on how to spot the camp, including a photo, had gone over the cliff, etc., etc.

In my field of classical music, there’s a device called counterpoint, in which the whole of the music is made up of intertwined melodies. This kind of music is called contrapuntal. From this point, our problems became a contrapuntal web of strangeness and incipient calamity.

We got onto the trail along the river before Elena and Jake. Given that Norm was manifestly stronger, we agreed that as we climbed away from the river I’d wear the daypack the rafters gave us, holding all our canteens, then on the flat I’d take over Norm’s hefty pack. We clambered up flesh-ripping volcanic boulders for an hour or so before we reached the flat and changed packs. It was early morning and we were mostly in shade, so I stuffed my hat in my pocket. At Garnet Canyon midway it’s reported to be hard to find the trail out, and indeed it took us a half hour of poking around to locate it. There were a couple of spots where you had to haul yourself up to a ledge with teetering rocks for a foothold.

After another couple of hours we came to a bit of shade to rest and have some gorp and a cautious amount of water. It was there that I discovered my hat had fallen out of my pocket. Being in Grand Canyon in the heat without a hat is not a good thing, not good at all. I leaned back on a rock and added it to the bad-news list. Norm had a bandana I could use, better than nothing but barely. About a half hour later who should arrive but Elena and Jake, who with a flourish produced my hat. He said they’d found it hanging on a bush beside the trail. The bush had probably jerked it out of my pocket. But after all this was good luck! Maybe our fortunes had changed!! (They hadn’t.)

We hung for a while. Elena and Jake seemed lovey-dovey. I saw her writing in his journal: “I [heart sign] you Jake.” Awwww, I thought. They left before us, heading for Copper Canyon. I gave them the best directions down to water there I could remember. We set out a bit later, then after a while found them in the shade again, looking bushed. It struck me that Norm and I seemed to be having less trouble with the heat than they were. We kept going and before long they passed us again.

By about 5PM, after nine miles of hot and heavy hiking, we arrived at Copper Canyon. We picked our way along the west side of the canyon, looking down anxiously for Bass Camp and water. No sign of it. Where the trail crossed the dry creekbed we found Elena and Jake sitting slumped and unhappy. They hadn’t found the way to Bass Camp either. But Jake had clambered down some ledges below and found skanky water in potholes. We needed that water, badly. And Jake had one piece of fabulous news: the rangers had emailed him and said they’d meet us at the rim at 7 PM tomorrow. We had a ride to civilization! Where we could attack the problem of retrieving the car. But 7 PM seemed plenty of time to hike out tomorrow. Plenty of time!! Plenty of time… But in the morning we had to confirm the rendezvous by email with Jake’s GPS gadget, or the rangers might not show up.

Norm was tired but he was still the stronger of the two of us, so he agreed to go down with Jake and fill up the canteens. Norm’s water filter was clogged and useless, but Jake had Elena’s filter and some nifty water treatment drops that would not remove the skank but at least purify it. With a packful of canteens they headed down.

Elena and I sat on the rock, dusk approaching. As we waited we chatted awkwardly. She said her flashlight was going dead and she didn’t have any spare batteries. (She’s an experienced hiker. Experienced hikers pack spare batteries.) That meant that the only surviving flashlight among the four of us was Jake’s, which he’d taken with him. As dusk arrived Elena’s chat got darker. I’ve had it with Jake, she said. But this afternoon you’d written I heart you! I reminded her. No I didn’t, she said. Anyway, it’s over. As dark came on the mood descended to deep gloom.

Finally it was some two hours since Norm and Jake had headed down. I was peering into the darkness with increasing concern. Finally I said to Elena, They could be in trouble. You’ve got a little flashlight power left, you need to go down and… I’m not going, Elena said. But they could be… I’m not going, she said.

A while more and I saw a pinpoint of light below. Jake and Norm didn’t arrive back for another half hour. They had been hauling water up tricky ledges and they were both exhausted. But they’d filled the canteens. Most of the water was raw and disgusting. Jake said Elena’s filter had clogged after a couple of liters (she had told us it never clogged), and the rest of the twelve liters or so was unfiltered skank.

At this point Elena was more or less hissing and spitting at Jake. He stayed glumly quiet, taking an occasional toot from a bottle of whiskey. He’d shared it before, but not now. Norm and I took stock. We had enough water to get up to the rim, barely—about nine liters though only one filtered, and we’d cached another liter partway up. We could use Jake’s purification drops on the unfiltered gunk. All the food we had left was a freezedried dinner for one, which had to be rehydrated with hot water from Jake’s stove. The four of us were down to one flashlight, Jake’s. Feeling our way in the dark, Norm and I unloaded our stuff across a boulder from them.

From that point things among us became, oh, let’s call it excruciating. Elena was calling Jake every name in the book. He was quietly hostile. In whispers, Norm told me that as they gathered water Jake had told him Elena has a bipolar condition that gives her wild swings of mood and affection. Every day is up and down, adore him and hate him. He loved her and wanted it to work, but she was a rollercoaster. As the evening went on Elena was hating on Jake noisily. As she cursed at him we had to ask, “Um, can we use your stove? And your flashlight for a few minutes?” Without getting actually insulting, Jake was putting out vibes that he had his own problems at this point and ours were no longer relevant. We didn’t press it. We already owed both of them a lot in terms of advice and help.

Then Jake told us he had dropped his GPS somewhere. He was fairly sure it was next to the water pockets down below, but anyway he didn’t have it. We weren’t as certain as he was. And without his GPS there was no email, so no way to confirm our arrival date to the rangers, thus we might have no ride for the 35 miles of desert road.

Then it transpired that Jake had also lost the single other thing we needed: his water purification kit. It was surely lying on the ground somewhere in camp, but again, that was no dependable thing, and we couldn’t waste our one functional flashlight looking for it . Norm and I had the one liter of good water Jake had pumped for us before the filter clogged. The rest of what we had was yellow water with brown crud in it that looked like some distilled essence of disease. Jake noted that drinking bad water usually takes a couple of days to make you sick, so maybe we’d have time to get to the rim before we started wanting to die. We were not reassured.

What in general Norm and I felt at this point was intensely apprehensive. But under the circumstances we stopped begging Jake and Elena for flashlight, stove, water, anything, and left them to their devices. Elena’s affections for Jake had gone over an emotional cliff. We climbed a boulder in the dark and tried to find our sleeping stuff and the bottle of good water among a welter of gear lying on the ground. Finally in desperation I started lighting matches, one at a time, holding each one down to our equipment until it burned my fingers, then lighting another. We couldn’t find the water bottle, couldn’t find Norm’s sleeping pad. That went on until the match striker was worn out. This is it. I thought. This is the pits. But it wasn’t the pits yet, not at all.

We found what stuff we could find. I scraped out a hole in the dirt for my backside, made a mound of dirt for a pillow, and we settled down for the night. Jake had told us they were going to sleep late next morning, but Norm and I needed to leave early. Generously, Jake said to wake him up and maybe in the daylight he could find his water purification kit. We tried to sleep. That was hard, because at that point the two things we most essentially needed, clean water and a ride from the rim, were both in doubt. Meanwhile for much of the night in their tent just above us Elena was weeping and wailing, and I don’t mean metaphorically.

Dawn. We pulled ourselves upright and packed our gear, such as it was. It was about seven miles to the rim, the last couple steeply uphill, but the trail was said to be good. Norm would take his pack, I’d haul the daypack with all the water, but my load was still far lighter than Norm’s. He didn’t complain about that or anything else.

We needed to wake up Jake and hope he could find his water treatment. Norm took care of that delicate business. Meanwhile I headed out to take a leak, and got lost. For the first time on a hike in my life, sweating, floundering-around lost.

My best guess is that because I’d never seen the area clearly in daylight, I didn’t have any points of orientation. Anyway, somehow I wandered away, couldn’t find the campsite or even the creek bed, and in classic fashion my increasingly anxious efforts to get back to camp only got me more lost. It’s crazy for someone who hasn’t been in that situation, but as I well knew, in the desert you can easily die this way, going out to have a piddle and becoming coyote fodder. Sometimes they don’t find the bones for years. Finally I had to do what I didn’t want to, scream for help. Besides the embarrassment, I did not want to wake up Elena and set off another round of tsuris. After a bit I heard Jake yelling back, remarkably far below me. Sheepishly I stumbled back to camp.

Jake had found his water treatment drops. He looked drained and distracted. He couldn’t believe I’d wandered off. I couldn’t either. I heaved a few sighs and sat down with the drops to treat our nine liters of water. On the first day on the way down, near where we cached water, we’d passed plastic jugs with some two gallons of water lying beside the trail on the Esplanade. We’d see that water again on the way up, but I considered it to be cached by somebody and therefore forbidden unless we were in life-threatening trouble. Anyway, in terms of water we’d be OK more or less. It was imperative to get up to the rim by 7PM because that was what we told Jake to tell the rangers—if, of course, he managed to find his lost GPS and email them to confirm we’d be there. With after all no choice, we presumed he’d succeed. And by the way, since we had no flashlight it was also imperative to get to the rim before dark, because there were ledges and other iffy bits on the trail. We’d gotten offtrack a couple of times on the way down, in full daylight. Even in summer it gets dark in the Canyon early, by about 7:30.

I started treating the skanky water in our canteens with Jake’s treatment as I’d remembered him doing with their water. I put in the two sets of seven drops from two little bottles, then waited fifteen minutes. After a half hour I thought to read the instructions, which told me I’d been doing it wrong: you mix drops from each little bottle in a cap provided, wait fifteen minutes, then pour it in the canteen. I started over again. To treat our water took some hour and a half, during which the temperature climbed steadily. We got going some two hours later than we’d planned.

The hike over to the meeting point of the Royal Arch and South Bass trails took some three hours. When we got to the South Bass, our way up to the rim, it was after 10 AM and over ninety degrees. We did what you’re supposed to do, hunkered down in the shade until 4 PM, when the temps usually start dropping and the sun is less fierce. It’s a blank existence, waiting out the sun. Usually it’s too hot to read or to think much. If you’re lucky you enjoy the landscape, watch the clouds. You try to doze, though you’re steadily having to move as your shade is invaded by the sun. As 4PM approached we filtered our water through Norm’s bandanna to remove the worst of the gunk.

Now it was 4 PM and we had some three hours to climb about 3 miles and some 2500 feet up to the rim to meet the ranger—if Jake had been able to email the rangers and one was there, which was anything but certain. We preferred not to think about that. We headed up the South Bass and fell into our usual uphill pattern: Norm being significantly fitter, lighter, and younger, he’d get ahead then stop and wait for me. So it went for an hour. About 5PM we met for another rest stop, then he headed up. He was still carrying his heavy pack. I was schlepping our steadily decreasing water supply in the daypack the rafters gave me.

Before long, hauling myself upward, I took stock and came to a depressing conclusion. My legs were doing all right, but my wind was lousy. I hadn’t really done enough aerobic training for the trip, and unlike other hikes my wind had not gotten better as I went. Through the previous winter I’d had a nagging bronchitis that kept me from exercising and generally afflicted my lungs. I suspect that had something to do with my wind in the Canyon. In any case, as I slogged upward it came to me that there was no way I was going to make it to the rim by 7 PM. After that, meanwhile, it was going to be dark and we had no flashlight, and the upper South Bass was too rough a trail to flounder around on in the dark.

I started shouting for Norm, who had forged ahead. He heard me, barely, and waited. Another few minutes and he would have been out of earshot. I caught up with him in what proved a rare patch of tree shade on the trail. I’m not going to make it in time, I said. You’re much faster than I am. You have to go up alone and meet the ranger. I’ll stay here and wait for a ranger to come and get me in the morning. (The possibility that there might be no ranger to meet him at the rim tonight had vanished from our calculations.)

At this point most hiking partners would have flipped. They would have called me a jerk, a quitter, an all-around so-and-so who’s putting it all on them and by the way had been responsible for losing my fucking pack. In fact at that point I felt like a jerk, a quitter, a wimp, an asshole. I knew I could make it to the rim, but there was no way I would make it before dark or anywhere close to the rendezvous time, and I’d run out of water hours before I got there. Meaning in any case I’d have to bed down on the trail somewhere, and I’d have a thirsty and wretched night of it. In the end, given what we knew at the time, whatever my sense of failure, at that point I was right about what needed to be done.

Norm vented none of those accusations. All right, he said, and that was that. We divided our stuff. He left me a liter and a half of water—enough, barely, if I stayed in the shade and didn’t hike—, a whistle, all his spare clothes, a bag of Goldfish and some granola Jake had given us (we’d had practically nothing to eat since splitting a half dinner the night before). I had my fleece blanket and a pile of dirt for a pillow. We shook hands. “God be with you,” I said. “And with you,” said Rev. Norm. And he headed up out of sight.

I was alone, eventually probably miles from anybody. Was I scared now? No, though a little apprehension was in order. I felt irrationally confident that a ranger would come to extract me in the morning. Was I bored in the next five hours before I could go to sleep? Not particularly. I was in a lovely glade, one of the few shady spots like that on the South Bass Trail. I sat on a rock for a while and looked down the creek canyon to the buttes in the distance. The word grandeur doesn’t begin to encompass it. I thought about life and love and music and books and eternity. Grand Canyon has taught me the joys of doing nothing for hours but looking and thinking, also not thinking but simply being.

What I needed not to think about was water. I paced myself to a couple of small sips from the canteen every hour. I tried to eat some goldfish and granola, but I was so dehydrated that I didn’t have enough saliva to get it down. The food ended up an obnoxious grainy crust in my mouth that lingered for hours. As dusk came on I took my time digging a perfect bed hole and shaping a pillow in the middle of the trail. This grubby expedient was starting to feel almost reassuring. Before I turned in I took a modest leak—reassuring since it meant I wasn’t completely dehydrated–, took an also modest sip of water—I was down to under a liter—and drifted off.

In the morning I got up to take another small reassuring leak and a sip of my remaining water. I luxuriated in my dirt bed for a while, trying not to count the minutes waiting for the ranger, trying not to think about water. Finally I was upright, sitting on my rock looking down the valley, enjoying the shade of the grove. I could have and as it turned out should have started hiking up in the cool of the morning. But I figured I’d run out of water and…anyway, I didn’t.

About 9:30AM, with a surge of excitement, I heard voices. I stood up, trying to look game and presentable. Around the corner came a couple. They stopped, smiling a bit uneasily for some reason, and said, “You must be the guy. We’ve got something for you.” They weren’t rangers, then, but they had something for me! They produced a half liter of Gatorade and a granola bar. The Gatorade was even a little cool! I forbade myself from guzzling it. They said rangers had asked them to give me the stuff, and they’d probably be down soon to get me. As we chatted I noticed they were still looking at me a bit sideways. I didn’t know why until that night.

They headed downtrail toward their camp at the river. I settled in confidently to wait, finished the last of the Gatorade before it lost its cool. I waited, trying not to look at my watch every other minute, trying without entire success to keep to my once-an-hour sipping regime. By 11AM there was less than a half liter left in my canteen. I waited. Waited waited waited waited.

By 1:30 PM I had a quarter liter of water left and had completely run out of thoughts. With nothing better to do, I started blowing distress signals with the whistle: tweet tweet tweet, wait ten minutes, do it again. I had been at this endeavor for about forty minutes when far up the valley I heard something that might have been somebody shouting my name. That, or a bird. I jumped up and screamed back. Another ambiguous sound, but it definitely seemed to be in answer to me. I chose to believe it was the ranger.

I had been imagining my ranger based on the ones I’d met over the years. It was going to be a bearded, burly guy in his forties. In his pack he’d be carrying a gallon or so of cool water and plenty of food for me. I entertained myself with these fantasies while I stood shuffling around in the middle of the trail. Ten minutes, twenty. A rustle from above. My ranger appeared around the corner.

It was a willowy, attractive young woman wearing a ranger uniform and hauling an enormous pack. She smiled helpfully, saying, “Hi! You’re Jan, right? I’m Kelly. How are you doing? You’re a lot further down than I thought.” As she asked the relevant questions I could see her professionally sizing me up. She was a little amused, I didn’t know why until that night. She called in on the radio and told them she’d found me.

Before long I realized that Kelly was not too impressed with me. I knew why. A good deal of the people she dealt with in rescues could not, like me, walk and talk. And if I could do those things, why was I needing her? Sure, I had very little water left, but it’s not like I was dying of dehydration. I’d have a couple of days before it came to that. And Kelly told me something I hadn’t realized: the gallons of water sitting on the Esplanade trail crossing were up for grabs, in fact may have been left for hikers by a ranger. Meaning: water left visibly on the trail is not assumed to be cached, so you take what you need.

Kelly also told me something that shrank my innards a bit, though actually I’d known it but neglected to think about it: Grand Canyon rescue resources are limited and each case is rated as to seriousness. Broken legs, heart attacks, falls off cliffs, severe dehydration, and various other calamities have priority over the likes of me. And those things happen all the time. So there had been no guarantee a ranger would have come for me today, tomorrow, anytime. Kelly came today because she was free and volunteered, not because she was assigned. She noted that she was getting overtime for the gig. I felt happy about that, at least. I did not dwell on the possibility that somebody might have needed her services worse than I did.

If I’d known all this, mainly about the water available on the trail, I would have been motivated to keep going to the Esplanade the day before. With that water I could have gotten to the rim well before today noon, around the time Kelly arrived at the trailhead.

Ah, well. Kelly was not impressed with me. I wasn’t either. But she was entirely professional, in a reassuringly chatty way. She handed me a half liter bottle of water and said to try not to drink too much, she didn’t have a lot on her. So much for my fantasy of a ranger lugging gallons. And there was a granola bar. As she stuffed my maimed hiking sticks in her pack and gave me two extras she had brought (!!), she told me that she was 22 and had been doing rescue work since she was 14. I was supposed to be reassured. I was.

We headed up, Kelly following me so I’d set the pace. We were headed for a bit of shade under a rock shelf she’d noticed, to wait out the heat. As we walked she noted breezily that if I broke down she would leave me by the trail to die. I understood this to be a joke. But I understood that I was expected not to crap out. Actually I felt reasonably strong, all things considered, and there were a lot of things to consider, having to do with less than ideal strength, lack of food, lousy wind, not enough water, age, and so forth and so on. But I was walking all right—better than she expected, Kelly told me. I clutched her praise.

We reached the shade under a ceiling of rock and sat down for two hours, filling the time with talk. Norm had gotten out the night before, she said , and was installed in a motel room waiting for me. I told her I am a musician. She told me about her boyfriend, about her trip to Ireland, about being first-chair French horn in her high school band. She hoped soon to get a job doing rescue with the Arizona Highway Patrol. All entirely cozy. Finally she announced that we could be quiet for a while, and that was fine too.

About 4PM we got going and I trudged up the trail in fairly decent form, considering. The trail was ledgy in places and that confirmed that I would not have wanted to be doing it in the dark without a light. When we arrived at the Esplanade trail crossing I made sure that Norm had taken our cached water, which he had. There was still a gallon of water sitting by the trail. I sat down and over 45 minutes downed a liter of it. With Kelly politely prodding I got up for the last, steep climb out.

On the way Kelly told me about one of her colleagues, an MD from Germany named Greta who turns up at the Canyon every spring for two months to do rescue work gratis, because she loves it. “If you look at her,” Kelly said, “you can’t tell whether she’s a guy or a girl.” But Greta is enormously clever and resourceful. “Basically she can figure out and fix anything,” Kelly said. It was an interesting story, to pass the time. Like so many things on this trip, it would turn out to be more significant than that.

We got to the parking lot after dark. I was thrilled to find that Kelly had lots of Gatorade in her truck. She turned onto the road, hit the first rut, and my head slammed into the roof. I asked her if maybe we could etc. and she slowed down. We got to the motel about 9:30. Kelly vanished, talking on her radio, before I could say goodbye and thanks again. The lady behind the desk gave me Norm’s room number. She was one more person looking at me quizzically. I was about to find out why.

Wrapping my fleece blanket around me, I trudged in the chilly night air to the room and knocked on the door. Norm opened it with great smile and gave me a hug, exclaiming that they’d told him I wouldn’t be back before midnight. He was babbling stuff about water, getting to the rim after dark, a German transvestite.

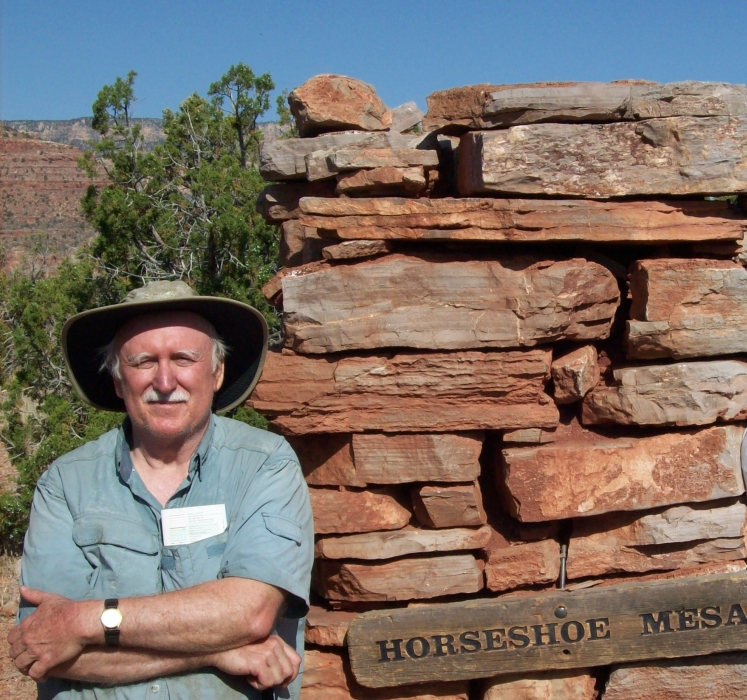

I wasn’t processing all this. “Wait,” I said, and went to take a shower. When I looked into the bathroom mirror I understood the sidelong looks I’d been getting. Normally in the later stages of a hike I look something like this:

What I saw in the mirror was this:

What I saw in the mirror was this:

Actually that picture doesn’t do justice to how grubby I really was. The word “filthy” does not encompass my state. Dirt was caked on my face, dripping from my hair, embedded in a week of whiskers. I looked dangerous, like somebody you’d run away from.

I took a sublime shower, put on clean clothes. (We had stashed our good clothes and travel stuff at the hotel.) As always at the end of a hike, my trail outfit had become instantly repulsive and was quarantined into a plastic bag until I could double-wash it at home. I sat down to a sandwich Norm had gotten for me.

As I ate Norm filled me in on the end of his trip. Though had he pushed it to the point of exhaustion he hadn’t made it to the rim by 7PM, the nominal rendezvous time with the theoretical ranger–if in fact Jake had found his GPS and contacted them, and if they had somebody available to come. Among other things, on the hike out it had taken Norm 45 minutes to find the water I’d cached on the Esplanade. At 8PM he was still below the rim and hiking in the dark without a light. When he saw the rim he decided to turn uphill and clamber up the slope because the top looked so close. It wasn’t. The clamber was a disaster, during which he lost both his poles. Norm ended up back on the trail for another ten minutes of climbing until he emerged at the parking lot.

To put it mildly his heart sank when he saw the dark shapes of a couple of vehicles but otherwise no sign of life. Then suddenly the headlights of a truck lit up and out leaped the aforementioned German transvestite, crying, “You must be de hiker I meet!”

It was the intrepid Greta. When Norm told her his wallet and cell phone were locked in the SUV, she confirmed her reputation by hauling out tools and spending the next 45 minutes jimmying the door. These vehicles are not supposed to be jimmyable, but in Greta they met their match. As soon as Norm had his cell in hand he called his wife Peggy. She answered and burst into tears. For two days she had been planning the funeral. Meanwhile as instructed she’d been trying to deal with the rental car company–Hertz, for the record–to try and get another electronic key sent. They had been utterly unsympathetic and unhelpful. The car has to be towed, they said. It’s too far out a bad road to be towed, Peggy said, and there’s been a dangerous situation that required rescue. Not our problem, Hertz said.

Norm could not imagine any tow truck getting the SUV out of there on that wretched road. He left with Greta, who took him back to a motel and a nice dinner at the hotel. Norm told me he that while he enjoyed his dinner and wine he thought with sympathetic concern of me below, sleeping in my dirt.

So I was back. In the motel we turned in. I slept quite well indeed. Next morning we got up and turned to the boggling questions of how to get the SUV out of the wilderness and how to get me on a plane without an ID. Norm had already changed our flight to a day later with USAir, for which they charged us $400 each (a fee which in the end they declined to refund because of the emergency, though there is supposed to be a provision for that).

We made another stab at getting a key sent from Hertz, citing the emergency again, and again getting no drop of help or even fake sympathy. With a sigh, we called a tow place in Flagstaff, 100 miles away. We described the situation, the guy agreed to try it. The price for the tow was going to be $700 whether or not it succeeded. By now between the tow, Norm’s lost poles, the extra night at the motel, and the new flight, he was out some $1000. So was I, plus the over $1000 of my gear that went over the cliff.

Next day around noon at the motel–I was now eating on Norm’s credit card–the tow guy arrived from Flagstaff. His rig was a big flatbed that looked even more hopeless to handle a rutty dirt road than a regular tow truck. Norm headed out with him while I busied myself getting a letter from the Rangers on formal letterhead explaining that I’d had an emergency, lost my pack, had to be rescued. I saw it as the equivalent of a letter from home for the teacher. I hoped it would get me past airport security, because I was such a pathetic case. I hoped they’d understand that if I were a crook or a terrorist I would not have made up such a ridiculous story.

In high anxiety I waited hours for the return of the tow truck. This was the first and most critical of the two major problems we had left. I had visions of the SUV being unextractable, our having to actually buy the vehicle, etc. Then about 2:30 there was the tow truck outside the window. And incredibly, the SUV gleaming on the flatbed.

We piled in to the truck and Norm and the driver recounted this episode of the saga. The driver had done some fancy maneuvering. He’d never seen anything like it, he said, in years of work at the company his father founded. A couple of times he’d had to extract himself from a rut by smashing down his car-lifting crane onto the road and rocking the truck until it popped free. He became our latest savior. Meanwhile on the way out they’d run into of all people Jake and Elena, heading home in their car, looking happy and once again lovey-dovey. They invited us to join them for dinner that night. We’ll let you know, said Norm.

In fact there was no chance for a reunion with Jake and Elena. We needed to get to Flagstaff that night in time to get a new electronic key made and drive to our hotel, then leave early next morning for our flight home. We arrived just as the dealership was closing. It’ll have to be done in the morning, the guy said, but I appreciate your problem and I’ll give you a deal on the key–only $325. (It is really, really not good to lose an electronic key.)

The tow guy dropped us at the hotel in Flagstaff. Things got uneventful for the moment. The Hotel Monte Vista names its rooms for actors who once stayed there on movie shoots back in the day. Somehow they always seem to put Norm and me in the Walter Brennan room. Walter being a grizzled-old-coot sidekick in Westerns. It was OK, though, because Norm can do an impressive Walter Brennan imitation in expressing, for example, our resentment over experiencing ageism and cootism.

Next morning we got a cab to the car dealer’s, shelled out for the key, headed for Phoenix, dropped the SUV off at Hertz with some unfavorable customer comments, then headed to Sky Harbor Departures with the last pack of anxieties about getting me on the plane. At the USAir desk I presented to the lady my nice official letter from the rangers. She sighed. “Go through security,” she said. “They’ll deal with it.”

We went through the lines and stood waiting for the security guy. He arrived, I showed him my ranger letter. He examined it grimly. “This doesn’t make any difference,” he said. “Wait here.” How long, we said. It could take an hour or more, he said. But we’ll miss… “Not my problem,” he said, and disappeared.

In the event he reappeared in fifteen minutes. He sat down at a computer, typed something, and began asking me the most remarkable questions. Where was I born? What make and model and year of car did I drive? What was the make and model of my previous car? And so forth. With each correct answer he became happier. Finally he stood up with a smile and declared I was free to go. It was our last kindness of a stranger. He patted me on the back and said, “Don’t drop any more packs off cliffs.” You bet, I said.

Norm’s wife Peggy picked us up in Boston, delighted to find us both and especially Norm alive and kicking. This isn’t the first time I’ve planned Norm’s funeral, she told me. They dropped me off and I hit the sack, two days away from my mattress being constituted of soil.

Next day I went to the camping store and starting replacing my gear. A few days later I called Norm and said I thought we should do the Royal Arch again next spring and for chrissake get it right this time. Okay, Norm said.

It’s March now. We leave for the Royal Arch Trail in a month. I’m in training, determined to be in better shape than last time. Just bought a new pack. All right, I’m a little bit nuts. Norm, bless his heart, doesn’t bring that up.