JAN SWAFFORD–

IN MEMORIAM: GANDY (ca. 1984)

I first set eyes on Gandy Brodie on a blustery day in November, as I was driving to my schoolteaching job in Vermont. There he was, hanging his thumb beside the road at West Townsend. I pulled over automatically – hitching was the only form of public transportation in that area–, then regretted it when I saw the shabby figure galloping toward me. “O Christ, a bum,” I groaned. As he neared the car I revised that estimate: surely this is another resident of the Brattleboro Retreat, out in a day pass, seeing the sights. As he opened the door and slid in I confirmed a mad light in those wide eyes.

As with all my hitchhikers there ensued a period of confusion, because my VW Beetle came equipped with detectors that detected the backside of anyone sitting in the car, and a buzzer that wailed until that seatbelt was fastened, and finding the seatbelt was not easy. Still, this stranger went beyond the usual bounds of incomprehension, totally unable to grasp my instructions, smiling in a really unsettling way at my groping around his person, looking game and crazy/friendly, until I had for the only time in my experience to get out of the car, go around, open the door and hand his belt to him. Then he couldn’t figure out how to fasten it.

Finally he was squared away, the banshee buzzer ceased, and off we set. Glancing over, I saw him smiling and staring fixedly ahead (retreat patient, all right) and holding a new artist’s brush tight in his fist. Trying with a certain sense of despair to break the ice, I asked, “So, you have a brush there. Are you an artist?”

“I’m a famous painter,” he said.

Like nearly everything Gandy said, that statement was susceptible of interpretation, had layers of versions of truth mixed in with ironies and outright fantasies. All this, of course, was just like his paintings, those layers and layers of speculations and revisions, all of it seemingly talked into place with his never-ending, fantastic, exhausting rap.

Gandy was and is famous and not famous. His paintings are in the collections of the Metropolitan Musician of Art and the Museum of Modern Art, among others, and he had significant admirers. One of the latter was critic Meyer Schapiro, who wrote of him, “Gandy Brodie stands out by his stubbornly personal poetic art… the arrested metaphors of insecure and frustrated existence…the purity and perfection of emerging life.” He had an extensive show in New York about fifteen years ago. For what it’s worth, I’m a middling dilettante of painting and I don’t know anyone of Gandy’s generation whose work I appreciate more. But as for famous: for a while I queried a number of painters and found no one who’d heard of Gandy Brodie. As the young aspiring composer I was when I met him, I hadn’t realized yet that there’s a substantial difference between good and famous.

But that elusive fame was important to Gandy, in the singular admixture of the sublime and pragmatic and incomprehensible that made up the color of his consciousness. He talked often about getting ahead, played the hustler, dropped more than a few names. Once when I was visiting his house he shoved before my eyes one of the stranger photos I ever saw. It was from his days as a hot young New York painter, I suppose, a picture from an old Vogue, maybe by Avedon, from sometime in the 50s. Posing in the photographer’s studio was a smashingly dressed Vogueish model of the era; beside her Miles Davis, trumpet in hand; and kneeling at their feet Gandy, holding one of his paintings and looking smug. That night he told me he had lived for some time with Billie Holiday, who was his greatest influence. I never found out to what degree that was true, but I began listening to Billie then and still do.

I get ahead of myself. The day we met, Gandy and I made our way down the road from West Townsend and sounded one another out. I told him I was a composer and at present was making my living teaching music at the high school in Townsend. “Then you teach my son Shane,” Gandy said, and so I did – my moony guitar-playing Grateful Dead head, Shane. Sure, of course. Gandy became a little interested in me: a fellow artist, a mentor for his son. He was to maintain that interest, despite my comparatively fledging creative career and my shy incapacity to cope with him. The thing was, you see, Gandy took everything seriously, which was one of the most nearly intolerable things about him. So if he was going to be interested in me he was going to lavish the blinding glare of that seriousness on whatever encounters we had. Always, I shrank from it. I’d never met anybody larger than life. I myself was just life-size.

I dropped Gandy off in Townsend and he aimed his thumb toward Newfane, where his studio was. Later that day I told Shane I’d met his father. “Pretty weird, huh?”, Shane said.

As best I can remember, I saw Gandy on six or seven further occasions over the next two years, the longest of them maybe two hours. But I felt then and still feel that he is as much a part of my experience as people I’ve known for years. It had to do with the density of our encounters. A meeting with Gandy was never a quick greeting or a simple get-together. It was an Event floating on the unceasing stream of his talk, which was an infinite dissertation on painting and the universe and one’s relation to them. I quickly discovered that it was impossible to banter with Gandy; every joke, every conventional ploy of conversation was absorbed into the labyrinthine processes of his mind and before my ears transformed into something rich, strange, and bewildering (bewildering, at least, to a young composer wrestling with the quotidian demands of art, a job, a new wife, and money). I have no samples of Gandy’s words to offer because I rarely could remember a thing he said. I only remember a musing voice, a rambling and weary rhythm, webs of ideas trailing off into obscurity.

Once he came to my place for a visit and I played scratchy tapes of two or three early pieces of mine, the only things that had been performed by then. He proclaimed them magnificent, which they were not, but I hoped his instinct about my artistic promise was at least a prophecy from what might be a bona fide prophet. Visiting his house I met his wife Jocelyn, herself a painter. “Jocelyn could’ve married Picasso, but married me instead,” Gandy told me later. As best I can figure, what created that notion was that Jocelyn, as a young and beautiful painter, had lived in Paris at the same time Picasso did.

Driving through Newfane on sunny days in the spring and summer I would pass Gandy painting in the yard outside his studio. I wish I’d stopped, but never did. I was too shy, he was busy (though I found that having a visitor never seemed to slow him down), and on sunny days in spring and summer I lacked the nerve to deal with him. Even in passing, though, I could see the somber and sprawling tapestry of his colors, him dancing before the canvas going at it with strokes sweeping or gentle.

I visited his studio only once. It was a barn piled with decades of paintings, most of them still in progress. On an old easel dripping with stalactites of paint sat a canvas. Like all his work it was representational, but done in a free and hyperexpressive style reminiscent of Abstract Expressionism. In the middle of the canvas was a figure, which in spite of the morass of paint one could somehow recognize as Gandy, holding his pallet–a self-portrait of the painter in late middle age. It was the background that was astonishing: it’d been redone so many times that it stood out nearly two inches from the canvas. His image in the center was buried as in a pillow by that swelling mass of paint. “It’s a wonderful effect!” I exclaimed. “It’s sheer incompetence.” Gandy said in his dreamy voice, painting as he spoke.

By that point he’d become a fixture in my dreams. Always he was a wild, prophetic figure, sometimes robed in white, a judge and a goad and a burden. Once I dreamed he was sitting in the rafters of his studio declaiming away, and we were down on the floor in tears, begging him to come down among us and paint again.

My memory of our next-to-last meeting is hazy. He’d called and asked to visit me where he was staying, teaching at some summer school. He wanted me to talk to his son, who had gone to college to major in music. Gandy wanted me to inspire Shane, or something. Nothing much happened; Shane was diffident, I didn’t know what I was supposed to do. Saying goodbye, Gandy suddenly kissed me on the lips.

The last time was in Brattleboro. I ran across him in front of the library where he was hitching. He asked me if I was going toward Newfane. I was not. He stood with his thumb out, talking away. I remember his broad and strangely handsome features under a dirty wool cap, his stocky, strong figure and shambling grace. I recalled him saying he had studied dance with Martha Graham. (I didn’t believe that, but apparently it’s true.) A pickup truck pulled over and the driver motioned him to get in back. Without ceasing his rap, Gandy clambered into the back of the truck and tumbled heavily to the bed, turning to continue his monologue to me. The truck drove away, his voice faded into the distance. I looked after it for a long time.

A year later I was back in Vermont for a visit, no longer a resident schoolteacher, now taking a crack at graduate school. I phoned Gandy’s house and got Shane, who told me what had happened: Gandy had gone to New York and on some back street dropped dead of a heart attack. By the time he was picked up his wallet was stolen. It was a week before Jocelyn found him in a morgue. He was 51. “His father and brother died the same way,” Shane told me. “It’s the curse of the Brodies.” So that darkness had been stalking him, shadowing his monologues. To Shane I said what one says, then for some reason asked about the self-portrait. “The figure turned into a tree,” Shane said, “but it’s him all the same.”

That was 1975. Dealers have some of his work, but I suspect a lot of Gandy’s paintings are still piled somewhere unsold. That’s what Jocelyn told me years after he died.

I don’t know how much of this recollection is true and how much I’ve imagined or dreamed. I still dream about Gandy.

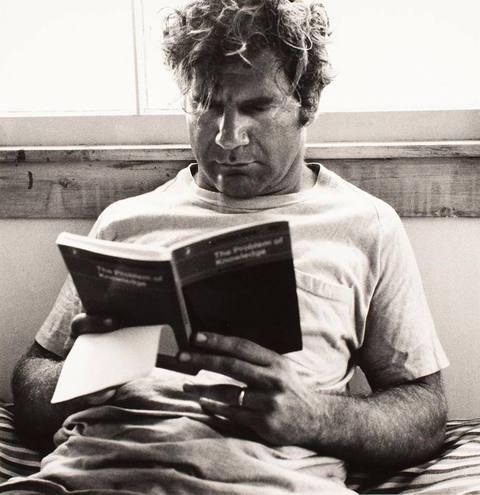

Note: A search online will turn up some things about Gandy, including a long interview that gives a taste of his style. On YouTube there are videos of a couple of shows of his work, and there are some paintings of his on Google Images. The above is the only photo of him I’ve found.