We biographers tend to write about people who are famous, who are powerful, who may be little-known but are still extraordinary. Here I propose to tour an imaginary biography of somebody who in the usual understanding of the word was entirely ordinary. But I have opinions about that.

Some background. On the whole, biographers are professional coattail-riders. We write about famous or important or unusual people because they’re the ones readers are most likely to be interested in. Having written biographies of Brahms and Beethoven, I’m familiar with this syndrome. My own opinion, though, is that if it’s done well, a biography of anybody at all would be just as interesting as one about somebody famous or important. It’s in that context that I want to talk about the biography I won’t be writing. Its subject would be my mother’s brother, my uncle Larry.

First a couple of convictions concerning my craft. I suppose most people look at biography as a literary interpretation of somebody’s life. That’s not how I see it. Given that we can never really understand anybody else, and for that matter don’t necessarily understand ourselves all that well, it seems to me unrealistic and morally dubious to interpret somebody else’s life at a distance, for our own benefit, when they’re not around to defend themselves. I think biographers need to respect the ultimate mystery of every human being. To me a biography is a narrative of a life, not an interpretation of it. The bits of interpretation I indulge in are things that in the course of a project become to me more or less obvious. If I want to interpret somebody I’ll write an essay, not a biography–to limit the damage to my subject.

In the same way, I don’t consider biography to be a literary form. I don’t think a person’s life has a literary structure, so I don’t try to cut and shape the details of my subjects’ life into a piece of literature. Life is not like a book. It’s more like a stumble in the dark, looking for the light switch. Life is a matter of rambling themes and variations rather than of logical structure. I want my biographies to be like that, which is to say, more like life and less like a book.

I also believe that each book should in its form, its style, its tone, be in harmony with the person it’s talking about. My first biography, of American composer Charles Ives, I hope encompasses some of his wildness and eccentricity, not just in its information but in its essence. Ives was involved in music and business and politics and philosophy and baseball, all in an inimitable way. So my bio of him had three different kinds of chapters; its voluminous endnotes include an illustrative and hilarious story about my high school band and a troubling anecdote I ran across—in an old Danbury newspaper–concerning Cotton Mather.

When I came to Johannes Brahms, I found a quite different kind of person, private and guarded, a relentless craftsman who spent most of his life simply writing and performing music, frequenting brothels, and fighting with his friends. An exemplary musician’s life, really. Brahms only experienced major drama during his early 20s, when as an unknown music student he was proclaimed the coming savior of German music by Robert Schumann, after which Schumann went round the bend and was institutionalized, Brahms fell in love with his pregnant wife Clara, and so forth and so on. In other words, a mess. After that it was apparent to me that Brahms wanted no more drama in his life, and he largely managed to avoid it. That biography was straightforward. When I got to Beethoven I was extensively concerned with the craftsmanship in his music, because that craftsmanship was profound and profoundly influential on the music that followed him. There the narrative inevitably involved the daily discipline of his art in contrast to the misery and incompetence of the rest of his life.

In these terms I’ll lay out here some of my never-to-be biography of Uncle Larry, concerning its points of interest and its (non-literary) structure. For starters, then, in this one I would naturally be more intimate and interpretive than usual for me, for the reason that I knew this man as part of my family, he lived in my neighborhood in Chattanooga, Tennessee. (If I had watched Brahms or Beethoven walk down the street and talked to them for five minutes, I would have written different books about them.) But again: if Larry was what is called an ordinary person, I believe that when you truly know someone, nobody is ordinary. The style would be engaged but in the middle distance, the way I experienced Larry all my life: even though he lived a mile away, we didn’t spend all that much time with him. After mother threw my alcoholic father out Larry made some efforts to mentor to my brother and me, but nothing much came of it.

Larry and my mother Lucille Swafford were born to a lower-middle-class family in the town of Riceville, Tennessee, population around 300. This was red-dirt, mostly redneck South, featuring decades-long feuds, casual racism, snake-handling churches out in the woods, and buggys and dusty hoarse motorcars and hand-crank phones of 1920s vintage and my grandmother’s daily eavesdropping on the party line.

Mother and Larry’s parents were more or less middle class, with a bit of let’s call it cultural ambition. In her teens in the 1920s my mother played Mozart and Debussy on the piano along with ragtime and boogie-woogie. My maternal grandfather Lawrence, whom we called Grampie, was in his youth a whiz at math and had been offered a college scholarship. But his betrothed, my grandmother Beulah, wept nonstop for two months until he capitulated: he would not go to college, he would marry her, he would work for the post office.

Grampie held the job of rural mail deliverer for some fifty years, making his rounds first in a horse and buggy, then in a Ford Model T, then in 1947 and 1954 Fords. He gave candy to the kids on his route and was admired around town as a good and decent man. I remember that Model T, sitting in a barn for years until some hunters bought it after making sure it would hold the dogs. Grampie was a deacon in the First Baptist Church for I don’t know how long. I remember his tremulous tenor in the choir. He had an unabridged Oxford Dictionary on a special stand in the living room, and when the preacher mispronounced a word in the sermon, Grampie let him know about it. Some preachers appreciated that, some didn’t. At least one sermon was preached against his meddling. Grampie survived to see the moon landing on TV.

The family dynamic with the children was this: My mother reigned as my grandfather’s favorite. Larry was the cutup, the one who got in trouble, who started smoking at 10. None of it amounted to anything wildly rebellious. Their mother, my grandmother Beulah, the daughter of an MD who became the town drunk, was the ultimate mom, cooking half the day, raising flowers, making costumes for her children’s theatrical productions on the columned front porch, and so on. (The Swafford house looked like a miniature Tara.)

Beulah was what you’d call a piece of work. In her youth she had wanted to be an opera singer. In her 50s she quit the church choir in a huff when they told her she was singing too loud, and she rarely went to church again. To maintain her complexion, for fifty years she kept her face covered in Vaseline. When you visited, she’d come running shrieking endearments like a madwoman and cover you with greasy kisses. Mother told me that in her coffin, she had beautiful skin. When Grampie was in his 70s and succumbing to Alzheimer’s, Beulah accused him of running around with hussies and locked him in the house. The day she reached for a cereal box on the shelf and dropped dead at 84, a widow living alone, she had been making Easter eggs that nobody but her would see. Except for Larry all the Swaffords have died at 84, as I expect to.

That is what Larry came from. One story he told me says a lot about him and Grampie. When Larry was young he and Grampie used to take baths together, because in those days you had to heat a lot of water on the woodstove. One day, I figure as a joke, Grampie decreed that they would begin their bath with a bucket of cold well water poured over their bodies. In the tub, Larry stuck it out when Grampie poured the water over him. When it was his turn, Larry poured and after the first splash Grampie vaulted out of the tub and took off running naked through the house, Larry sprinting after him lugging the water. When Grampie reached the front door, his hand on the knob, Larry caught up and gave him the whole bucket. They laughed about it for the rest of their lives.

Another story Larry told me: As a teenager he took to driving to nearby Athens, another small town but big enough to have a pool hall. When Grampie found out Larry was shooting pool he said, “I’m not going to forbid you from doing it. But I want you to take a drive with me.” Grampie drove Larry to the pool hall and they stood in the back, watching the rowdy, obscene proceedings from a distance. Finally Grampie said, “Do you want to be that kind of person?” Larry didn’t. He never went back.

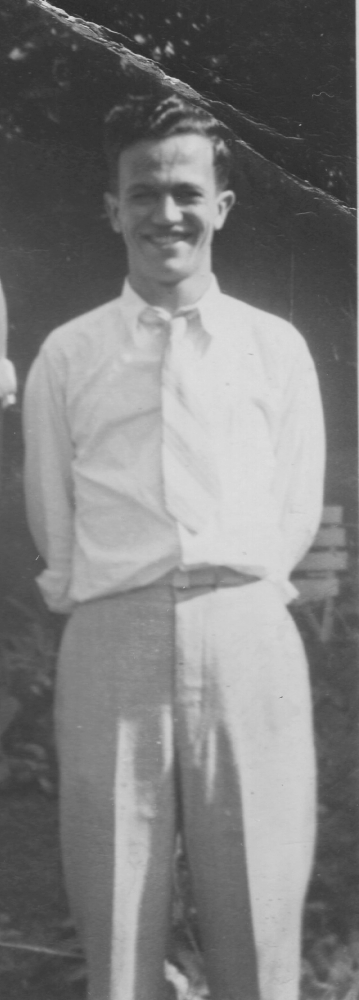

Above all what marked Larry’s youth was that he was marvelously and kind of strangely handsome. He looked unlike anybody else in the family. As a biographer I know that how you look can have a considerable influence on your life. In his youth Brahms was strikingly good-looking, blonde and blue-eyed, and that had something to do with the way people responded to him. Beethoven was homely and solipsistic and chronically ill, and that played its part in his life and his inability to find a wife. In later years one woman Beethoven had courted recalled simply: “He was ugly and half crazy.”

In his teens Larry played halfback on the Charleston High football team and reigned as the school heartthrob. My mother told me he averaged six calls a night from girls. (In her teens my mother Lucille was pudgy, Daddy’s girl, played violin, did not get in trouble, did not get calls from boys. Her one piece of rebellion was her marriage, and that didn’t work out so well.) But Larry’s looks were odd. He had curly black hair, big lips, an olive complexion. In my book, his singular attractiveness would begin an arc of story that has to do with the South in midcentury, and with race. This arc is not a literary construction. It played out that way.

The other thing about Larry was that he was a born tinkerer with an instinctive understanding of gadgets under his hands. Like a certain number of curious kids he would take apart the family radio. Unlike most kids, he put it back together and it still worked, and he knew why. That gift created his career as an engineer, with jobs verging on big time if never quite. My grandmother taught piano; I remember Larry pulling out her keyboard and taking it home to fix it. Piano repair was nothing he had studied. He just looked over the mechanism and figured it out.

Grampie was determined that his children would go to college. In his years at a small Methodist school Larry was not much of a student, but inevitably he was popular and became head cheerleader. When he first caught sight of Doris the homecoming queen he said to a friend, “I could fall in love with that girl like that,” and he snapped his fingers. He did fall in love with her, and she with him.

In old photos from the tennis court they are a gorgeous couple, like movie stars. After college and the Army, Larry married Doris. He had spent the war working on planes in the Pacific. One day, he told me, the Enola Gay landed at his field. They knew it was doing something big, but they didn’t know what it was until they heard about Hiroshima.

After the war Larry and Doris came back to Chattanooga and he got the first of a string of good engineering jobs. They fell into what appeared to be the 1950s American dream of respectability and prosperity. I remember their living room full of matching blonde furniture and a distinctive smell of warmth and contentment. Everybody we knew in the 50s wanted to get married and have kids, to make a nice living and live in a nice house, to look good in church: to be normal.

Larry and Doris had two girls, Jeanne and Terry, who got pretty dresses and dancing and music lessons and lots of stuff. Since my home was that of a divorced schoolteacher struggling to get by, every Christmas I was painfully aware of how many more presents my cousins had under the tree than my brother and I did. Also how much nicer Larry and Doris’s house was, how much longer their driveway, how they had a big garage and a grand lawn. Every birthday I heard from my mother: “You’ll get your birthday present at Christmas.” After the opening of the Christmas presents, Larry taking photos with his fancy camera, the generations always had a big dinner in our house, presided over by Grampie. I remember Larry year after year, playing with his kids’ Christmas toys with intricate delight.

In my memory Larry in his prime is always brash, busy with his hands, building a putting green in his yard and tinkering in his garage workshop, shirtless in summer, proud of his physique. In middle age he was as handsome as in his youth, with the same grand smile. He laughed a lot, played golf (in youth he was good enough to think about going pro), told racy jokes at holiday dinners, grilled steaks every summer on the patio he built. In his later career he had a good job in a factory that made boilers for nuclear submarines. One day he showed me a part he had machined and compared it to the same part made by somebody else, explaining to me how his showed more skill, more attention to detail, more pride. That was the most enduring thing he ever said to me. He made no secret of his prejudices. When I told him I’d gotten new roommates in college his first words were, “Are they white?” One of them isn’t, I said. “I’m disappointed in you,” he said. “Don’t tell your Uncle John.” His point was that John, who in childhood was called Sweet Jan and after whom I’m named, was a bigger racist than he was.

My family was mostly racist, in the casual and unthinking way of that time in the South. But in the way of middle-class Southerners they were perfectly polite to black people. One day that politeness got Larry in trouble, as he saw it. He had told some black co-workers about his home putting green; they wanted to see it and piled in his car. I remember him knocking on the door and my Mother opening it to Larry crying, “Lucille, I’ve got six niggers in my car! What am I going to do?” I don’t remember what the solution was to this crisis of humiliation before the neighbors. A lot of how you behaved in those days concerned what the neighbors might think.

I have to skip forward now. My book would at last reach the point when it became manifest to all of us that everything to do with Larry was a crumbling wall of deception. In those days in Wasp families in the South, such things were not spoken of until they had to be. The answer to distress was generally to sweep it under the rug. Larry’s wife would have realized it first, then the kids, then my mother, then his coworkers.

I think that deception says something about the delusions of normality and respectability that marked the 50s, how superficial and hypocritical they so often were. To mention one thing, in the South of the 50s they were still lynching black people with impunity. In the seventh grade in 1958 I watched the president of the ninth grade class pulling chains out of his locker to go downtown and beat up black kids during the race riots. Meanwhile the industrial pollution in Chattanooga was so bad that on sunny days downtown in summer women’s’ stockings were known to dissolve. A friend and I used to sit on a bridge over Chickamauga Creek and watch raw sewage float downstream.

There are secrets and there are secrets. Some are harmless, some harmful only to their owner, some harmful to the people you love the most. In short, through all Larry’s respectable, laughing, family-sitting-together-in-church-on-Sunday life, there was a secret that I suspect was not spoken of until it became unavoidable: Larry was a secret and serious drinker. My cousins Jeanne and Terry told me later that neither of them could remember anything in their lives before high school. They had blanked it out because of Daddy.

In our family alcohol was anathema, not to be countenanced or anyway admitted. Larry was sly about it. He drank vodka out of the bottle, so it wouldn’t show so much on his breath. He stashed bottles all over the house and in his workshop. I remember he always smelled somehow medicinal; at night his face was red and he moved and spoke slowly. He still had the smile, for a time. His employers liked and respected Larry and kept him on as long as they could. Eventually they had to let him go.

Finally it all hit the fan. Larry crashed the car in his driveway and fractured his skull. Doris refused to deal with it, so it fell to my mother to take him to the hospital. There she watched her brother go through DTs. She thought back to their childhood, Larry the brash talented teen heartthrob. All the hope, all the fun. She told me it was the worst night of her life. And she had divorced my father mainly because he was alcoholic. I remember how Larry looked in the next years, gaunt and withdrawn, not meeting your eyes. My brother said to me once: “For all our family’s teeth-gritting attempts at respectability, we turned out quite a pack of loonies.” There was an underlying strain of fundamental decency, which mainly flowed from Grampie. Yet the family floated on a tide of lies and half-truths.

To make the long sad story short, Larry got on the wagon, fell off, in the end managed to stay sober. He never admitted he’d been alcoholic. But in his last years the big smile, the joie de vivre, the brashness and confidence were gone. He sat in his workshop making little stained glass pieces and rebuilding an old Model T. His wife and my cousins became fanatically religious. Mother said: “I feel so sorry for Larry stuck in that house full of women praying all the time.”

Then he died. Lung cancer, from the smoking. But that’s not the end of the biography. In my book the climax would come after he died.

One day not long after Larry was buried my brother and I were visiting our cousins when out of the blue Terry said to me, “Did you know that when both Jeanne and I were born, Daddy was terrified that we’d come out black?” My brother and I were thunderstruck. His widow had just walked in and I blurted, “Aunt Doris, is that true?” “Yes,” she said. “Isn’t that funny?” And she walked out.

I’ll leave it there, with the unanswered questions that moment raises. Did Larry know something about Grandmother Beulah the rest of us don’t? In childhood had he been teased about his dark complexion and big lips and curly black hair? What does all this add up to, in the relentlessly respectable, conformist, indelibly racist world of the South in the 1950s?

Which brings me to my final point. A person is made in part by his or her surroundings, so a biography is not only a portrait of a person but of a time, a place, an era, an ethos, all of them working for well and for ill on everybody. So my portrait of Larry would also be a portrait of white Anglo-Saxon America from the 1930s to the 1970s, from country to city, from lynching to marching, from horse and buggy to moon landing.

I think Larry’s story could make a nice book, a biography of a fascinating ordinary man who was felled by ordinary tragedies and by the webs his time and place snared him in. But nobody in it is famous or important, nobody would read it, and I don’t intend to write it.